Studies suggest that children who rely more on vision from their left eye could be more likely to develop dyslexia if they learn to write using pathways in the right brain hemisphere. Dr David Mather, a researcher at the University of Victoria, recently published a paper reviewing these findings. He outlines a proposed approach to teaching writing skills that could prevent these children from developing dyslexia. This approach involves teaching children to write when they are 7 or 8 years old, when the human brain is better at mapping and memorising entire words. More

Dyslexia is a language learning impairment that affects approximately 10 to 15% of people worldwide. People diagnosed with dyslexia typically find it difficult to read and write, as they might struggle to remember letters, place them in a different order when writing words, or forget their pronunciation.

These difficulties with reading and writing can have a significant impact on the lives of affected individuals, as they can slow down their progress in school and at university, or even prevent them from smoothly completing daily tasks that involve reading or communicating with others in written form.

Neuroscientists and psychologists have been trying to identify the root causes of dyslexia, as this could help in devising interventions that support dyslexic children. While there are now more resources designed to support people with dyslexia throughout education, most of these do not help affected individuals to fully overcome their linguistic difficulties.

Dr David Mather at the University of Victoria recently published a paper that reviews recent research exploring the neural underpinnings of dyslexia, while also outlining a teaching approach that could reduce the risk that children will develop this language impairment.

In his paper, Dr Mather explains that dyslexia manifestations can be divided into two primary subtypes, known as phonologically deficient and phonologically proficient. People with the first type of dyslexia appear to decode language by looking at the shape of letters. Therefore, they are more likely to use certain letters with similar shapes interchangeably – such as ‘d’ and ‘b’. People with the second type, on the other hand, appear to primarily memorise letters and words based on their sound.

Some studies show that children who often confuse the shapes of letters and their order in words also have difficulty drawing continuous figure-eight loops, as they tend to involuntarily reverse the direction in which they are drawing. Interestingly, when blindfolded and initially guided in their hand movements by a teacher, their ability to draw these loops significantly improves.

According to Dr Mather, a new hypothesis has emerged in recent years about why some children might start to develop dyslexia.

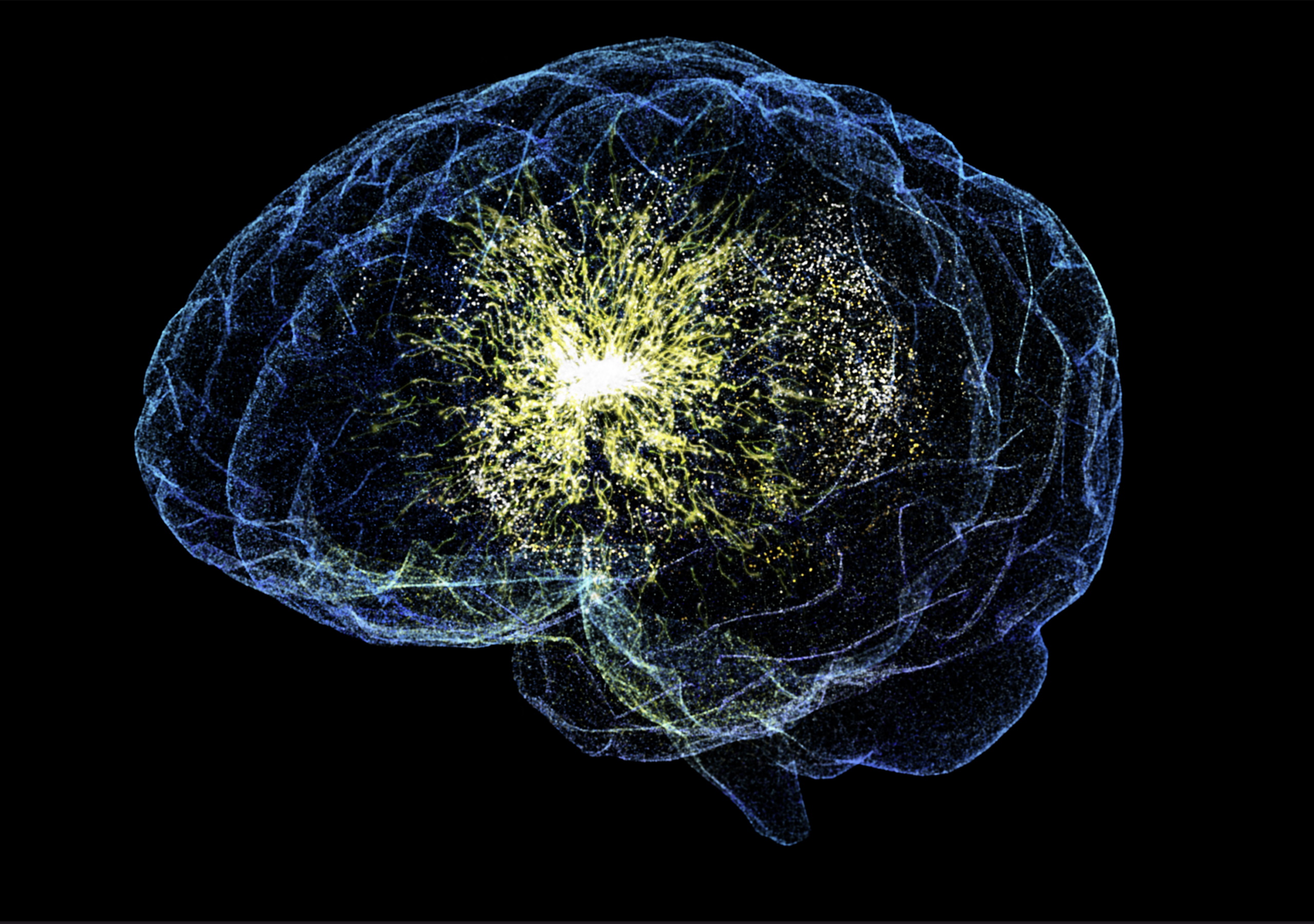

Just like some people are right-handed and others left-handed, individuals tend to innately rely more strongly on one of their eyes for vision. While the left eye is connected to the right hemisphere of the brain, the right eye is linked to the left hemisphere. Interestingly, studies show that children with a dominant left eye who learn to write using the right hemisphere of their brain can experience difficulties with ordering and discerning some letters.

These difficulties may be linked to the position of the corpus callosum, a large set of nerves connecting the left and right hemispheres of the brain. The order and orientation of these nerves appears to be the reverse of how most Western languages are written and read: from left to right.

A dominant right eye and the primary use of the brain’s left hemisphere while learning to write could allow children to compensate for the unfavourable position of this nerve-based structure, enabling them to learn reading and writing more easily from a young age. On the other hand, children with a dominant left eye who primarily use the right hemisphere while learning to write might experience problems with reading and writing words from left to right.

Dr Mather explains that this hypothesis is now supported by a considerable amount of experimental evidence. For instance, some studies found that dyslexic readers exhibit an increased communication from the right to the left hemisphere through the corpus callosum, while others found that the structure of the corpus callosum itself differs significantly between dyslexic and non-dyslexic readers.

Interestingly, young children with a dominant left eye have shown superior performance to their right-eye dominant peers when in learning Hebrew, which is written and read from right to left.

Before the age of 7 or 8, most children primarily try to make sense of the world though ‘proprioception’, which describes the body’s innate ability to sense movements and its own position in space. After this age, however, the brain learns to better integrate proprioception with vision, which could facilitate a dyslexic child’s learning to read and write.

Based on these findings, Dr Mather recommends that children should be taught to read and write at the age of 7 or 8, to prevent those with a dominant left eye from developing dyslexia. This delayed education could also be beneficial for right-eye-dominant children whose first language is written from right to left, such as Hebrew, Arabic and Kurdish.

Before such widespread changes to our education systems are possible, Dr Mather hopes to inspire educators and language therapists to postpone reading and writing lessons for children who exhibit the early signs of dyslexia.